NIST has some interesting articles on their website, one of them being a 5 MHz phase detector with low residual flicker [1] for measuring phase noise. This spurred some discussions and a series of measurements on my part.

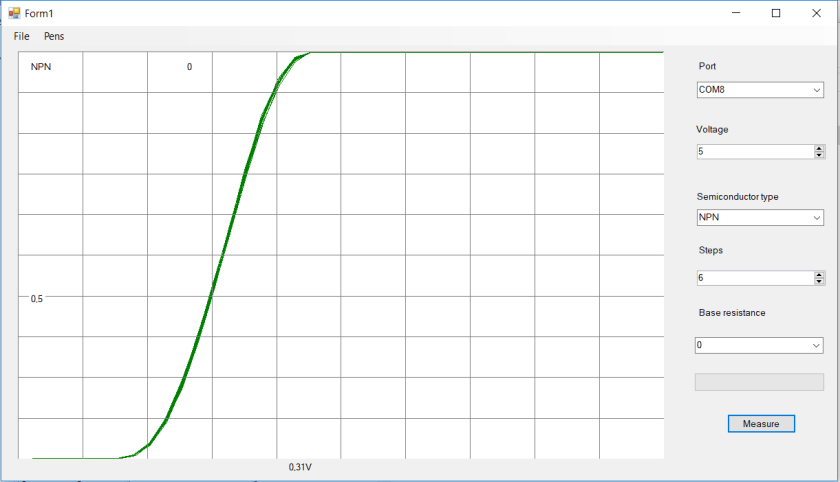

The interesting part is the usage of common 2N2222 transistors. There have been some discussion on the internet about the outlined connection of the transistor as a diode with the BC junction shorted. Some claiming it behaving as a switch, while others claiming it to be a diode. My own suspicion was that this would act as a diode, and a mixer was built tusing BC547B’s. A quick look at my crude curve tracer shows the diode action:

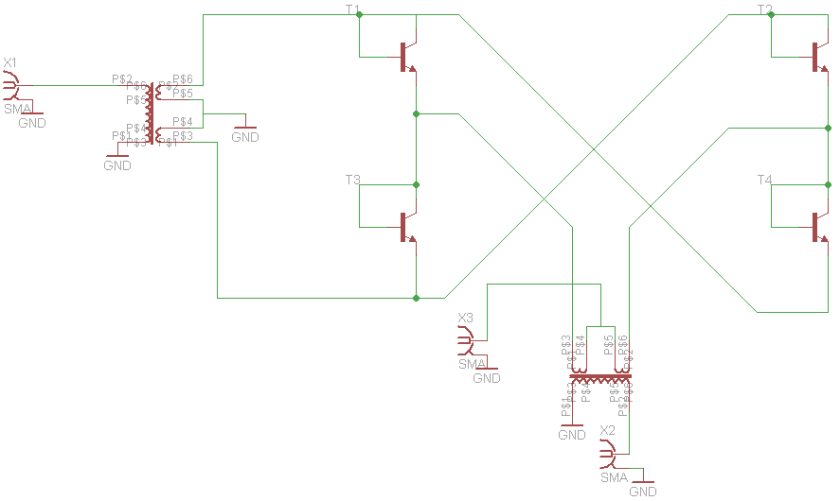

The mixer uses a 5:1 transformer for optimal impedance match, and I was not able to find a pair in my junkbox. Using FT-2402-43 cores, with a 2t primary, and a bifilar 4.5 turns secondary winding. 4 diode connected transistors and the mixer is working.

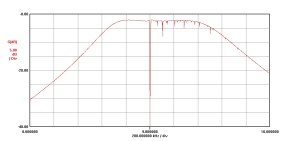

Mixing action was verified on a spectrum analyzer before compression points were measured used the 30% am technique.

As can be clearly seen, as long as the diodes are conducting, the mixing action is linear. With the low LO amplitude of 0dBm, the diodes are not conducting properly and that can be shown on the plot of the linearity. Notice that the mixer is in compression with as low as -8dBm input level. The bend and slope with 17dBm LO is somewhat larger than for the lower amplitudes, indicating that the mixer LO may be excessive. Some spectrum analyzer plots showing the IMD products should give further insight into this, if used as a mixer.

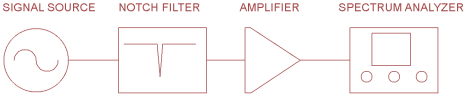

As a last test, I did try to use this phase detector to measure phase noise, using my current setup. Unfortunately there was little change compared to the much more noisy level 7 mixer it has. This is due to the noise in the low noise amplifier that follows the phase detector and masks any improvement in the phase detector for now. A new, 100pV/sqrt Hz input noise amplifier is planned.

[1] https://tf.nist.gov/general/pdf/2554.pdf

Note 18 nov 19:

Did a measurement of IL vs LO level at different frequencies:

Note 22 june 2020: