Over the past few months, considerable work has been done with the NanoVNA, an excellent compact vector network analyzer that performs well up to around 300 MHz. However, the available dynamic range is somewhat limited, comparable to that of an HP8410 at 10 GHz. The following measurements were performed to evaluate an original NanoVNA-H4.

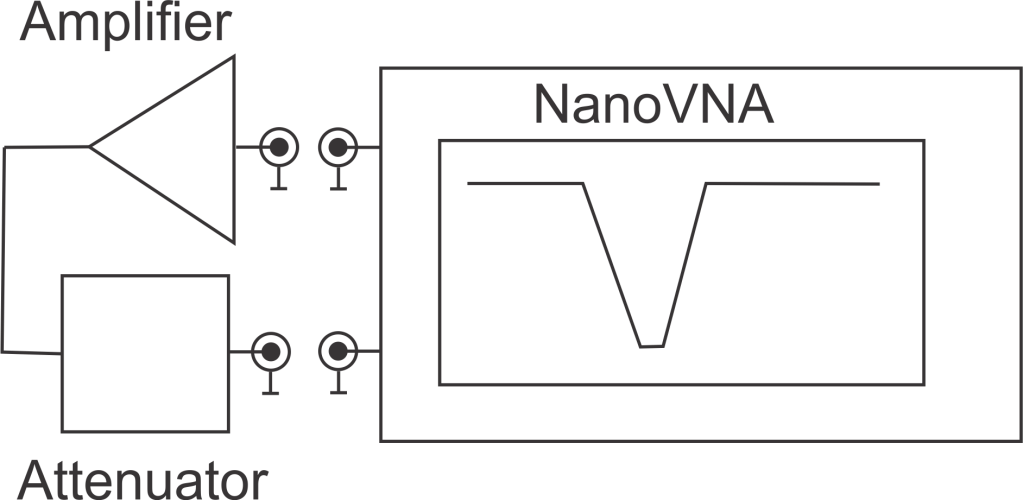

One challenge encountered was when measuring amplifiers. For a portion of the amplifier’s range, there was clear evidence of compression. But was it the VNA, the amplifier, or some other factor causing it? This led to the development of a setup to measure the compression point of the NanoVNA.

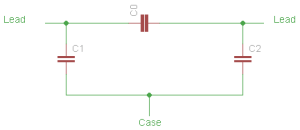

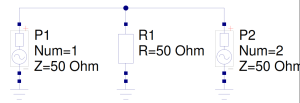

The setup included the NanoVNA, calibrated using a SOLT (Short, Open, Load, Through) procedure, with the shortest possible coaxial cable to ensure a 0 dB S21 response. A proper amplifier (Mini-Circuits ZFL-1000H) was used, terminated with a 6 dB attenuator, followed by a programmable attenuator. The amplifier’s output was measured at a single frequency while adjusting the attenuator. This ensured that the input level to the amplifier and the impedance remained consistent across all measurements, minimizing inaccuracies.

A Python script controlled the process, automating the reading of the NanoVNA, adjusting the attenuator, and taking new measurements. The NanoVNA’s power mode was set to “AUTO” during these measurements, as it was found to provide more consistent power compared to manual output settings.

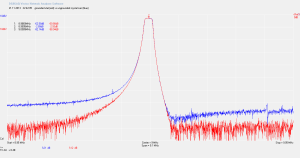

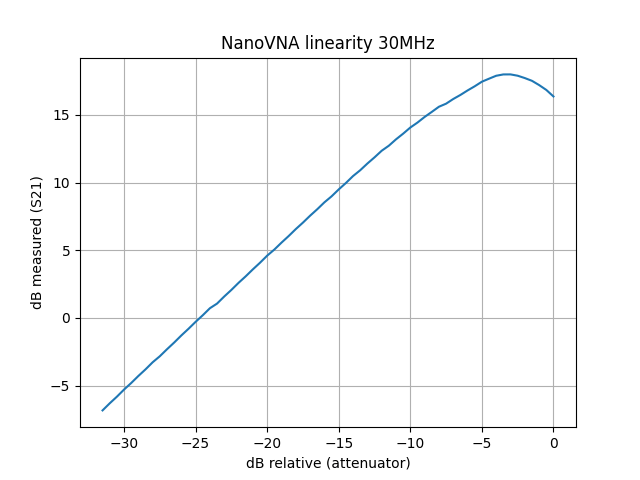

The results are as follows:

The data is plotted with the attenuator value on the X-axis and the measured output on the Y-axis. At HF frequencies, the results were satisfactory. It is generally safe to measure an amplifier with up to 10 dB gain connected directly to the VNA, but for amplifiers with higher gain, either the VNA’s output power should be reduced, or an external attenuator should be used on port 2. Above 200 MHz, there was little change in the compression point until around 300 MHz, where the VNA begins using the third harmonic for detection. As expected, this resulted in a lower compression point.

The disappointing part occurred above 600 MHz, where the VNA relies on the fifth harmonic. Here, the compression point decreased with increasing frequency. Interestingly, there was a specific power level at which the reported output was -24 dB. This value was consistently observed, and after multiple tests with different amplifiers and attenuators, it was determined to be an actual response of the NanoVNA, not a measurement artifact.

For those using the NanoVNA to measure amplifiers, it is recommended to proceed with caution when dealing with amplifiers that have high gain. Be sure to adjust the VNA’s output power or include external attenuation to avoid distortion in the measurements.